Up Country

Library and Archives Canada, Royal Canadian Mounted Police Collection

View of train and passengers at Vladivostok railroad station, spring 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

Few of the Canadians ventured “Up Country,” to the Siberian interior, where the White Russian forces of Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak battled the Red Army in the Ural Mountains. Divisions amongst the Allies, political tensions on the Canadian home front, and a growing “partisan” guerrilla movement convinced the Canadian government against a troop movement inland.

In December 1918, an advance party of fifty-five Canadians travelled along the Trans-Siberian Railroad to Kolchak’s capital city, Omsk, serving as administrative staff for 1500 British troops and preparing for the arrival of the main body of the Canadian force.

Credit: Canadian War Museum, George Metcalf Archival Collection

A train rounds the rugged shore of Lake Baikal, the world's deepest lake, eastern Siberia, c. 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

Smaller groups of Canadians travelled the same route bringing supplies and munitions for Kolchak’s armies. This included Captain Harold Ardagh, a 38-year-old accountant from Barrie, Ontario, who commanded a munitions train “Up Country” to the wilds of the Siberian interior in the spring of 1919. Capt. Ardagh's eigth-week adventure conveys the chaos along the Trans-Siberian Railroad and the factors leading to the failure of Allied Intervention in Russia.

“Up County” was an elusive place, a site of danger and mystery for the problem-plagued Siberian Expedition.

Advance Party to White Siberia

On 8 December 1918, fifty-five Canadians left Vladivostok on the train of Sir Charles Eliot, British High Commissioner in Vladivostok. They were under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas “Sid” Morrisey, a twenty-eight-year-old engineer from Montreal. Morrisey led the small party of eight officers and forty-seven enlisted men on the 4,300-kilometre journey to Omsk — to administer Britain's 25th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, and to arrange “supplies and billets for the main body of the force to follow.”1

Stephenson Family Collection, Burlington, Ontario

Members of the Canadian Advance Party proceed “Up Country” to Omsk. The promised reinforcements never arrived, as the Allies' failed to secure their line of communication: the Trans-Siberian Railroad.

View more photos like this in the archive

The Canadian Advance Party left Vladivostok with two months’ supplies, passing through Harbin, China and stopped at the city of Chita, where the Ataman General Grigori Semionov ruled. As British diplomat Eliot wrote after a meeting with the White Russian commander: "Considerable quantities of goods are imported by Semenoff and sold in two stores which he has opened... [They are bought by] speculators who retail at higher prices."2

Morrisey's party reached Omsk — capital city of Kolchak's White Russian government — on the afternoon of 27 December 1918. They arrived at a moment of tension, after a Bolshevik uprising that had been suppressed by “unnecessarily harsh measures” — the summary court martial and execution of several hundred insurgents, which inflamed the local population. The Bolsheviks, armed with forged documents, had staged an early-morning raid on the local prison, liberating and arming the inmates, and then seized the Kulomsino rail station and Kolokolnikov Mill south of the city, and blew up part of a bridge over the Irtysh River. White Russian authorities responded by marching 200 hundred suspected Bolsheviks across the frozen river where they were shot en masse.3

Canadian War Museum, George Metcalf Archival Collection

View down a main street in Omsk, capital city of Admiral Kolchak's White Russian government, c. 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

The Canadians' arrival at Omsk created conflict between Morrisey, a young officer, and Colonel John Ward, commander of the British troops in the city. Ward, a Labour Member of Parliament, had grown accustomed to operating autonomously and resented his subordinate position in Elmsley’s Canadian brigade. As Ward recalls:

Revolutionary plans in connection with the distribution of my battalion, and other matters, were instantly proposed. Some of them were actually carried out, with the result that a strained feeling became manifest in the British camp at Omsk, which caused me to propose to Brigadier-General Elmsley that my headquarters should be transferred to Vladivostok.4

John Ward, With the "Die-Hards" in Siberia (London: Cassell, 1920)

British troops stand for inspection before the Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Omsk, c. February 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

The Canadian troops at Omsk remained in a state of limbo as the Allies vacillated over the future of the Siberian Expedition and White Russians grew restless. British troops had evicted refugees to secure sleeping quarters, and the Canadians opened a small hospital and supply depot at the local yacht club. Kolchak’s minister of the interior had urged the Omsk Town Council to adapt a local theological school for barracks space, anticipating the arrival of the Canadian army in a "short time."

According to Morrisey, it was "manifestly unfair" to reserve barrack space at Omsk when it remained unclear whether the main body of the CEFS would ever reach the city. Elmsley capitulated, instructing Morrisey to "cancel [the] order regarding the reservation of barrack accommodation at Omsk ... until ... future policy has been definitely decided."5

Bryant Family Collection, Nanton, Alberta

Canadian soldiers, members of "B" Squadron Royal North West Mounted Police, stand with Russian children in a shanty-town of dug-out homes, Omsk, Siberia, Russia, c. 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

In January 1919, the Canadian command still believed that the main body of the CEFS would proceed to Omsk. The Bolsheviks in Siberia were "not a formidable adversary for even a small well-organized force," Britain’s high commissioner insisted. Canadian troops could perform garrison duty in the towns between Irkutsk and Omsk without "running much more risk than if they remained in Vladivostok."6

That month saw a heavy concentration of White Russian troops along the Ural Front — the mountain range that divided Europe from Asia. However, the tide began to turn in Siberia in the face of the instability on the Allies' "line of communication" — the only connection between Vladivostok and the Ural Front: the Trans-Siberian Railroad.

PROFILE

Capt. Harold Ardagh and the Trans-Siberian Railroad, Spring 1919

Stephenson Family Collection, Burlington, Ontario

Bridge destroyed by Bolsheviks in the Siberian interior. Dozens of attacks like this one in early 1919 paralyzed the Allies' line of communication and contibuted to the evacuation of Siberia. This photograph was taken by Pte. Edwin Stephenson en route to Omsk.

View more photos like this in the archive

Captain Harold Ardagh and eleven Canadians pulled out of Vladivostok’s central railroad station on 23 March 1919, aboard the 32-car transport train code-named Echelon 2051. A 38-year-old accountant from Barrie, Ontario, Ardagh was bound for the Siberian city of Omsk, responsible for shells, grenades, railway parts, and clothing for the faltering White Russian forces of Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak, former commander of the Czar’s Black Sea Fleet.

Ardagh and his men encountered a raff of problems along the Trans-Siberian Railroad: a fire in one of the boxcars loaded with shells and fuses; the disappearance of the locomotive outside Harbin, China; an accident where a Canadian sergeant was run over by a railcar and lost both legs; a week-long halt in the middle of Siberia when the tracks were “destroyed by Bolsheviks.”

Ardagh observed “burnt railway stations” and “a number of train wrecks,” as irregular partisan units sabotaged the Allies’ communications lifeline between the Ural Mountains and the coast.7

Canadian War Museum, 20030011-001

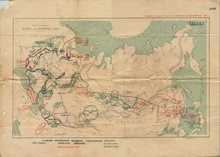

Map of Russia showing troop concentrations and areas of partisan strength, c. 1918.

View more photos like this in the archive

It took four weeks for Ardagh's train to cover the 4,300-kilometre distance from "Vladi" to Omsk. Ardagh delivered the munitions cargo for Kolchak's forces, then took two weeks exploring the city and commisserating with the small Canadian force stationed there. He attended a concert in Omsk’s modern opera house and church services at its large cathedral. The mood of the British Military Mission was “optimistic,” Ardagh observed, with Kolchak preparing to take command at the front and move his headquarters to Yekaterinburg: “The impression is that the Allies will be in Moscow by the 1st of August, and that it will be ‘all over’ before the winter. I have my doubts, but nous verons [we shall see].”8

In May 1919, Harold Ardagh returned to Vladivostok, as the last Canadian units evacuated the interior, exchanging fire with Bolshevik insurgents en route to the Pacific Coast. A month later, a train carrying five Mounties and 150 horses from the RNWMP was wrecked along this volatile section of track, the victim of Bolshevik sabotage.

Library and Archives Canada, Royal Canadian Mounted Police Collection

View of railcar being derailed by partisan bomb, Trans-Siberian Railroad, spring 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

Ardagh's experience demonstrates the hazardous journey “Up Country” and the instability that led to the Allies’ defeat and Canada’s evacuation from Russia. About two dozen Canadian-led transport trains braved the 4,300-kilometre journey from "Vladi" to Omsk in the winter and spring of 1918-1919. The most damaging trip saw the train Echelon 2209 wrecked when partisans opened fire en route to Ekaterinburg.

Nineteen boxcars were “smashed to atoms," while two White Russians and 18 RNWNP horses were killed, in an action that resulted in the awarding of service medals to RNWMP Farrier Sergeant J.E. Margetts and Corporal P.S. Bossard. Up the line, Czecho-slovak troops “captured and hung 26 of the Bolsheviks that wrecked [the] train, including the chief wrecker.” As one of their RNWMP colleagues informed the force commissioner in Regina: “this is claimed on good authority to be the longest journey ever undertaken and completed by any British horses.”9

Special Feature:

Notes:

- 1 Operation Order No. 1, 6 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S); Massey, When I Was Young, 211; MacLaren, Canadians in Russia, 165.

- 2 High Commissioner (Chita) to High Commissioner (Vladivostok), 18 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), app. 31; Instructions to Lieutenant-Colonel T.S. Morrisey, 7 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), app. 9; “Operation Order No. 1,” 6 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), December 1918, app. 1. See also diary entries, 8 December to 27 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S).

- 3 “Military Situation, December 31st, 1918,” War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), app. 117; “Twelve Executed for ‘Red’ Uprising,” British Columbia Federationist, 3 January 1919; High Commissioner (Omsk) to Acting High Commissioner (Vladivostok), 30 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S).

- 4 John Ward, With the “Die-Hards” in Siberia, 156; Beattie, “Canadian Intervention in Russia,” 321-22.

- 5 War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), 4 and 5 January 1919; “Pribitiye Kanadskih voysk” [Arrival of Canadian Troops], Pravityel'stvyenniy vyestnik (Omsk), 28 December 1918, Khabarovsk State Archives; War Diary of Force Headquarters, CEF(S), 3-11 January 1919; Morrisey to Elmsley, 15 January 1919, War Diary of Force Headquarters, CEF(S), January 1919, app. B8. See also Kinvig, Churchill’s Crusade, 209-10.

- 6 High Commissioner (Omsk) to Acting High Commissioner (Vladivostok), 9 January 1919, app. 19, Lash to Mewburn (via Elmsley), 13 January 1919, app. 39, Morrisey to Elmsley, 13 January 1919, app. B5 (all in War Diary of Force Headquarters, CEF[S).

- 7 Harold Vernon Ardagh Diary, 23 March 1919-4 May 1919, LAC, Ardagh Fonds, MG 30, E-150, files 2/6 and 3/6.

- 8 Ardagh Diary, 23 March 1919-4 May 1919, LAC, Ardagh Fonds, MG 30, E-150, files 2/6 and 3/6.

- 9 Constable G.H. Pilkington to RNWMP Commissioner, n.d. (1919); Captain Montague Smith to Commissioner RNWMP, 11 August 1919; “Diary of Echelon. 2209”; (all in LAC, RCMP Fonds, RG 18, vol. 3179, file G 989-3 [vol. 2]).

Go to

L'intérieure du Pays

Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, Collection de la Gendarmerie Royale du Canada

Vue d'un train et passagers dans la gare de Vladivostok, printemps 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Peu de Canadiens osa s'aventurer dans l'intérieur sibérien, où les forces russes Blanches de l'Amiral Alexandre Vassilievitch Koltchak combattirent l'Armée Rouge dans les montagnes de l'Oural. Les divisions entres Alliés, les tensions politiques et domestiques canadiennes, et le nombre croissant de « partisans » Bolchéviks guérilla convainquirent le gouvernement canadien de ne pas envoyer leurs troupes à l'intérieure du pays.

En décembre 1918, un détachement de cinquante-cinq Canadiens voyagea le long du Chemin de Fer Transsibérien à la capitale de Koltchak, Omsk, et siégèrent comme personnel administratif des 1500 troupes britanniques et préparèrent l'arrivée du corps principal des forces canadiennes.

Musée canadien de la Guerre, Collection des Archives George Metcalf

Un tour de train sur la côte tortueuse du Lac Baïkal, le plus profond au monde, en Sibérie orientale, c. 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

De petits groupes de Canadiens voyagèrent cette route pour apporter des vivres et munitions aux armées de Koltchak, incluant le Capitaine Harold Ardagh, un comptable de 38 ans, originaire de Barrie, en Ontario, qui commanda un train de munitions dans l'intérieure sibérien au printemps 1919. L'aventure de huit semaines du Capitaine Ardagh illustre le chaos le long du Chemin de Fer Transsibérien et les facteurs qui menèrent à l'échec de l'intervention des Alliés en Russie.

L'intérieure fut un endroit difficile à atteindre, dangereux et mystérieux pendant l'expédition Sibérienne.

Parti d'Avance en Sibérie Blanche

Le 8 décembre 1918, cinquante-cinq Canadiens quittèrent Vladivostok à bord du train de Sir Charles Eliot, Haut-Commissaire britannique à Vladivostok. Ils étaient sous le commandement du Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas "Sid" Morrisey, un ingénieur de vingt-huit ans, originaire de Montréal. Morrisey fut leader des huit officiers et quarante-sept troupes qui partirent sur la longue route vers Omsk — 4300 kilomètres — pour administrer le 25e Bataillon de la Grande-Bretagne, le Régiment de Middlesex, et organiser « les provisions et les billettes pour le corps principal de la force à venir ».1

Collection de la famille Stephenson, de Burlington, en Ontario

Le Parti d'avance canadien procéda à Omsk, mais les renforts promis n'arrivèrent jamais car les Alliés négligèrent de sécuriser leur ligne de communication: le Chemin de Fer Transsibérien.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Le Parti d'Advance canadien partit de Vladivostok avec des provisions pour deux mois, en passant par Harbin, en Chine et s'arrêta à la ville de Tchita, qui fut sous le contrôle du Général Ataman Grigori Semionov. Le diplomate britannique Eliot écrit à propos d'une réunion avec le commandant russe Blanc: « Des quantités considérables de marchandises sont importées par Semenoff et vendus dans deux magasins qu'il a ouvert ... [Elles sont achetées par] des spéculateurs qui les vendent à prix élevés ».2

Le groupe mené par Morrisey atteignit Omsk — capitale du gouvernement russe Blanc de Koltchak - l'après-midi du 27 décembre 1918. Ils arrivèrent à un moment tendu, à la suite d'un soulèvement Bolchévik supprimé par « des mesures inutilement sévères » — la cour martiale et l'exécution sommaire de plusieurs centaines d'insurgés, qui indigna la population locale. Les Bolchéviks, avec de faux documents, avaient organisés un raid sur la prison locale, libérant les détenus et les armant, puis saisirent la gare Kulomsino et l'usine Kolokolnikov au sud de la ville, et fessèrent finalement sauter une partie d'un pont sur l'Irtych. La réaction des autorités russes Blanches fut de faire marcher 200 personnes suspectes d'être Bolchéviks l'autre côté de la rivière gelée où ils furent fusillés en masse.3

Musée canadien de la Guerre, Collection des Archives George-Metcalf

Vue d'une rue principale d'Omsk, capitale gouvernement Blanc de l'Amiral Koltchak, c. 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

L' arrivée des Canadiens à Omsk fut cause de conflits entre Morrisey, un jeune officier, et le Colonel John Ward, commandant des troupes britanniques dans la ville. Ward, un député du Parlement pour le Parti « Labour », avait l'habitude d'être autonome et fut indigné par sa position subalterne dans la brigade canadienne d'Elmsley. Ward se rappela que:

« Des plans révolutionnaires relatifs à la distribution de mon bataillon, et d'autres questions, furent immédiatement proposées. Certaines suggestions furent effectivement réalisées, avec le résultat que la mauvaise volonté est devenu apparente dans le camp britannique à Omsk, ce qui m'incita à proposer au Brigadier-Général Elmsley qu'il me transfère à Vladivostok ».4

John Ward, With the "Die-Hards" in Siberia (London: Cassell, 1920)

Inspection de troupes britanniques devant la cathédrale Orthodoxe russe d'Omsk, c. février 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Les troupes canadiennes à Omsk restèrent dans un état d'incertitude car les Alliés vacillèrent sur l'avenir de l'expédition en Sibérie et l'inquiétude de Russes Blancs s'empira. Les troupes britanniques expulsèrent les réfugiés pour s'assurer des dortoirs, tandis que les Canadiens ouvrirent un petit hôpital et un dépôt de provisions au club nautique local. Le Ministre de l'Intérieur de Koltchak demanda au Conseil de la ville d'Omsk de convertir l'école théologique local en baraque pour accommoder l'arrivée de l'Armée canadienne qui était attendu « d'un moment à l'autre ».

Selon Morrisey, il fut « évidemment injuste » de réserver des baraques à Omsk lors d'une période d'incertitude quand il n'était toujours pas évident que le corps principal de la FECS allait atteindre la ville. Elmsley abdiqua, instruit Morrisey d'« annuler [l'ordre] concernant la réservation de baraques à Omsk ... jusque ... une décision définitive fut prise concernant nos objectifs ».5

Collection de la famille Bryant, Nanton, en Alberta

Soldats canadiens, membres de l'Escadron B de la Royale Gendarmerie à Cheval du Nord-Ouest, avec des enfants russes dans un bidonville de maisons creusées, Omsk, Sibérie, Russie, c. 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

En janvier 1919, le commandement canadien continua à croire que le corps principal de la FECS procédera à Omsk. Les Bolchéviks en Sibérie « n'étaient pas un adversaire redoutable pour une petite force bien organisée », insista le Haut-Commissaire de Grande-Bretagne. Les troupes canadiennes pourraient effectuer la garde des villes entre Irkoutsk et Omsk, sans « courir un risque plus élevé que si elles restèrent à Vladivostok ».6

Ce mois a vu une forte concentration de troupes russes Blanches le long du Front Oural - la chaîne de montagnes qui sépare l'Europe de l'Asie. Toutefois, l'instabilité de la « ligne de communication » Alliés se transforma en désavantage — le seul lien entre Vladivostok et le Front Oural: le Chemin de Fer Transsibérien.

PROFIL

Le capitaine Harold Ardagh et le Transsibérien, printemps 1919

Collection de la famille Stephenson, de Burlington, en Ontario

Pont dans l'intérieur sibérien détruit par des Bolchéviks. Des dizaines d'attaques comme celle-ci paralysèrent la ligne de communication Alliées au début de 1919 et contribua à l'évacuation canadienne de la Sibérie. Cette photographie fut prise par Pte. Edwin Stephenson lors de son séjour vers Omsk.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Capitaine Harold Ardagh et onze Canadiens sortirent de la gare centrale de Vladivostok le 23 mars 1919, à bord du train de 32 wagon portant le nom de code « Echelon 2051 ». Un comptable de 38 ans, originaire de Barrie, en Ontario, Ardagh était en partance pour la ville sibérienne d'Omsk, et responsable des obus, grenades, pièces de chemin de fer, et vêtements pour les forces défaillante russe Blanches de l'Amiral Alexandre Koltchak, ancien commandant de la flotte tsariste de la mer Noire.

Ardagh et ses hommes rencontrèrent une série de problèmes le long du Chemin de Fer Transsibérien: un incendie dans un des wagons plein de cartouches et de fusibles; la disparition de la locomotive près de Harbin, en Chine; un accident où un Sergent canadien fut écrasé par un wagon et perdu ses deux jambes; l'arrêt pour une semaine au milieu de la Sibérie où la voie fut « détruit par les Bolchéviks ».

Ardagh observa des « gares brûlées » et « un certain nombre d'épaves de trains », car des unités de partisans Bolchéviks avaient sabotés la ligne de communications des Alliés entre les montagnes de l'Oural et la côte est.7

Musée canadien de la Guerre, 20030011-001

Plan de la Russie montrant les concentrations de troupes et les zones de forces partisanes, c.1918.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Après quatre semaines le train dArdagh parcouru finalement les 4300 kms entre « Vladi » et Omsk. Ardagh livra la cargaison de munitions pour les forces de Koltchak, puis explora la ville pour deux semaines et compati aux malheurs de la petite force canadienne qui y fut stationnées. Il assista à un concert dans la maison d'opéra moderne d'Omsk et des services religieux dans la grande cathédrale de la ville. L'attitude de la mission militaire britannique fut « optimiste », observa Ardagh, lorsque Koltchak s'apprêta à prendre la commande du Front et de déplacer son quartier général à Ekaterinbourg: « L'impression est que les Alliés se rendront à Moscou pour le 1er août, et que « tout » serait fini avant l'hiver. J'ai des doutes, mais nous verrons ».8

En mai 1919 Harold Ardagh retourna à Vladivostok, comme les dernières unités canadiennes évacuèrent l'intérieur en échangeant du feu avec les insurgés Bolchéviks en chemin pour la côte est. Un mois plus tard, un train transportant cinq gendarmes et 150 chevaux de la RGCN-O fut déraillé dans cette partie volatile, victime de sabotage Bolchévik.

Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, Collection de la Gendarmerie royale du Canada

Vue des wagons qui furent déraillé par une bombe partisane, Chemin de Fer Transsibérien, printemps 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

L'expérience d' Ardagh démontre le danger de l'intérieure du pays et l'instabilité qui conduira à la défaite des Alliés et à l'évacuation canadienne de la Russie. Environ deux douzaines de trains dirigées par le Canada bravèrent le voyage de 4300 km de "Vladi" à Omsk en hiver et au printemps de 1918-1919. Le voyage le plus destructif vu le déraillement de l'Echelon 2209 en route vers Ekaterinbourg lorsque des partisans ouvrirent le feu.

Dix-neuf wagons furent « réduits en atomes », et deux Russes Blancs et 18 chevaux de la RGCN-O furent tués, dans une action qui aboutie à l'attribution de médailles de service aux Sergent Forgeron J.E. Margetts et le Caporal P.S. Bossard de la RGCN-O. Plus loin dans la ligne, les troupes tchécoslovaques « capturèrent et pendirent 26 des Bolchéviks qui déraillèrent le train, y compris le chef de la bande ». Un de leurs collègues de la RGCN-O informa ainsi le commissaire de la force à Regina: « Ce fut déclaré par une source fiable le plus long voyage jamais entrepris et complété par des chevaux britanniques ».9

Source spécial:

Notes:

- 1 Ordre d'opération n. 1, 6 décembre 1918, Journal de guerre du quartier général de la FECS; Massey, When I Was Young, 211; MacLaren, Canadians in Russia, 165.

- 2 Haut-Commissaire (Tchita) au Haut-Commissaire (Vladivostok), le 18 décembre 1918, Journal de guerre du quartier général de la FECS, app. 31; Instructions au Lieutenant-Colonel T.S.Morrisey, 7 décembre 1918, Journal de guerre du quartier général de la FECS, app. 9; « Operation Order n. 1 », 6 décembre 1918, Journal de guerre du quartier général de la FECS, décembre 1918, app. 1. Aussi les entrées de journal du 8 au 27 décembre 1918, Journal de guerre du quartier général de la FECS.

- 3 « Military Situation, December 31st, 1918 », Journal de guerre du quartier général de la FECS, app. 117; « Twelve Executed for ‘Red’ Uprising », British Columbia Federationist, 3 janvier 1919; Haut-Commissaire (Omsk) au Haut Commissaire par intérim (Vladivostok), le 30 décembre 1918, Journal de guerre du quartier général de la FECS.

- 4 John Ward, With the “Die-Hards” in Siberia, 156; Beattie, « Canadian Intervention in Russia » 321-22.

- 5 Journal de guerre du quartier général de la FECS, 4 et 5 janvier 1919; « Pribitiye Kanadskih voysk » [arrivée des troupes canadiennes], Pravityel'stvyenniy vyestnik 28 décembre 1918, Archives d'État de Khabarovsk, Journal de guerre du quartier général de la FECS, 3-11 janvier 1919; Morrisey à Elmsley, 15 janvier 1919, Journal de guerre du quartier général de la FECS, 1919 janvier, app. B8. Aussi Kinvig, Churchill’s Crusade, 209-10.

- 6 Haut-Commissaire (Omsk) au Haut Commissaire par intérim (Vladivostok), le 9 janvier 1919, app. 19, Lash à Mewburn (via Elmsley), 13 janvier 1919, app. 39, Morrisey à Elmsley, 13 janvier 1919, app. B5 (tous dans le Journal de guerre du quartier général de la FECS).

- 7 Journal d'Harold Vernon Ardagh, 23 mars 1919-4 mai 1919, BAC, Fonds Ardagh, MG 30, E-150, les fichiers de 2/6 et 3/6.

- 8 Journal d'Ardagh, 23 mars 1919-4 mai 1919, BAC, Fonds Ardagh, MG 30, E-150, les fichiers de 2/6 et 3/6.

- 9 Gendarme G.H. Pilkington au commissaire de la RGCN-O, s.d. (1919); Capitaine Montague Smith au commissaire de la RGCN-O, le 11 août 1919; « Journal de l'Echelon. 2209 »; (tous dans la BAC, les fonds de la GRC, RG 18, vol. 3179, dossier G 989-3 [vol. 2]).

Sauter à

Внутри страны

Библиотека и архив Канады, коллекция Канадской королевской конной полиции

Вид пассажиров и поездка у Владивостокского ж/д вокзала, весна 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Мало кто из канадцев решился отправиться вглубь России, в центральную Сибирь, где Белые русские силы во главе с адмиралом Колчаком сражались с Красной армией на Урале. Однако разногласия среди союзников, политическая напряженность внутри Канады и растущее партизанское сопротивление убедило канадское правительство отказаться от дальнейшего продвижения войск по России.

В декабре 1918г. передовой отряд из пятидесяти пяти канадцев отправился по транссибирской железной дороге в столицу Колчаковского правительства г. Омск для ведения административной работы в штабе британского контингента (1500 солдат) и подготовке прибытия основных канадских сил.

Канадский военный музей, коллекция Джорджа Меткалфа.

Дорога вдоль самого глубокого в мире озера Байкал, 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Небольшие группы канадцев ездили этим же путем, поставляя амуницию и продовольствие для армии Колчака. В одной из таких групп был капитан Гарольд Арда, 38-летний бухгалтер из г. Бэрри, пров. Онтарио, он командовал поездом с военными грузом весной 1919г. Капитан Арда на протяжении восьми недель пути в Омск был свидетелем полного хаоса, царившего по Транссибу.

Так что, канадское название для Сибири «внутренняя страна» было опаснейшим и таинственным регионом для канадских экспедиционных сил.

Предварительный отряд для Белой Сибири

8 декабря 1918г. 55 канадцев отправились из Владивостока на поезде британского высокопоставленного комиссара во Владивостоке Чарльза Элиота. Отряд был под командованием 28-летнего лейтенант-полковника из Монреаля Томаса Моррисейя. Отряд состоял из восьми офицеров и сорока семи солдат, им предстоял путь в 4300 км. Для того, чтобы наладить «продовольственные поставки для последующих канадских военных сил».1

Коллекция семьи Стефенсона, г. Барлингтон, Канада

Канадский передовой отряд отправляется в Омск. Обещанное подкрепление никогда не прибыло, поскольку союзники провалили операцию по безопасности на Транссибе.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Канадский передовой отряд отбыл из Владивостока с двухмесячным запасом провианта в Омск через китайский город Харбин, затем путь проходил через Читу, где власть принадлежала атаману Григорию Семенову. Британский дипломат Элиот после встречи с Семеновым писал: «Значительное количество товаров добытых Семеновым, продаются в двух магазинах, которые он открыл… Эти магазины купили спекулянты, где продают товары по более высоким розничным ценам».2

Отряд Моррисейя прибыл в Омск, столицу белого правительства Колчака, после полудня 27 декабря 1918г. Они прибыли в напряженный момент после большевистского восстания, которое было подавлено «неоправданно жестокими мерами»: военный суд приговорил к расстрелу несколько сотен большевиков, которые лишь воодушевляли местное население. Эта карательная акция была предпринята после того, как утром ранее, группа большевиков, вооруженная поддельными документами, осуществила налет на местную тюрьму. Освободим вооруженных заключенных, большевики захватили железнодорожную станцию в Куломсино и там же Колокольников комбинат, затем взорвали часть моста через реку Иртыш. Белые власти ответили расстрелом двухсот подозреваемых большевиков посреди замерзшей реке.3

Канадский военный музей, коллекция Джорджа Меткалфа

Вид на главную улицу Омска, столицу белорусского правительства адмирала Колчака, 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Канадское прибытие в Омск создало новый конфликт между молодым офицером Моррисейем и полковником Джоном Уордом, командующим Британскими военными силами в городе. Уорд, член Лейбористской партии в парламенте, уже привык вести все операции автономно, поэтому его возмутило решение о переходе под командование канадского отряда Элмслея. Уорд вспоминал:

Только что мне были представлены революционные планы, касающиеся распределения моего батальона и других дел. Некоторые из этих планов уже стали приводиться в исполнение, что вызвало напряжение в британском лагере в Омске, для меня это послужило причиной предложить бригадир-генералу Элмслея передислоцировать мой военный штаб во Владивосток.4

John Ward, With the "Die-Hards" in Siberia (London: Cassell, 1920)

Осмотр британских войск перед кафедральным собором в Омске, февраль 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Канадские войска в Омске оставались в подвешенном состояние из-за колебаний союзников по поводу будущего сибирской экспедиции и растущего беспокойства среди белого движения. Британские войска выселяли беженцев для того, чтобы обеспечить себя спальными местами в Омке, тогда как канадцы по прибытию открыли небольшой госпиталь и склад в местном яхт клубе. Ожидая прибытия канадцев, министр внутренних дел колчаковского правительства призвал Омский городской совет адаптировать «в короткие сроки» Епархиальное училище для проживания пятидесяти пяти канадских военных.

По мнению Морисейя это было «крайне несправедливо» - подготавливать казармы в Омске, когда прибытие основных канадских сил в Сибирь было под большим вопросом. В итоге, Элмслей был вынужден дать инструкции Мирисейю: «отменить приказ о резервирование казарменных помещений в Омске… до того момента… когда политическое решение будет окончательно принято».5

Коллекция семьи Браянта, г. Нантон, пров. Альберта

Канадские солдаты (эскадрон «Б» Северо-западной Королевской конной полиции) вместе с русскими детьми в беднейших трущобах Омска, 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

В январе 1919г. канадское командование продолжало верить, что основные силы Канадских экспедиционных сил отправятся в Омск. Большевики в Сибири «даже представляя собой небольшие, хорошо организованные силы не были серьезными противниками», - утверждал Британский комиссар. Канадские войска могли бы выполнять гарнизонную службу между Иркутском и Омском без «большего риска, чем, если бы они оставались во Владивостоке».6

В том же месяце наблюдалось большое скопление белых русских сил вдоль уральского фронта. Не смотря на то, что вся Сибирь была под властью белых, союзникам приходилось наводить порядок вдоль всей транссибирской железной дороги, на «линии связи», между Владивостоком и Уралом.

Очерк

Капитан Гарольд Арда и Транссибирская железная дорога, весна 1919г.

Коллекция семьи Стефенсона, г. Брлингтон, пров. Онтарио

Разрушенный большевиками мост в центральной Сибири. Десятки атак подобно этой вначале 1919г. парализовали линию коммуникаций союзников. Эта фотография была сделана Эдвином Стивенсоном на пути в Омск.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Капитан Гарольд Арда и одиннадцать канадцев отправились в путь из главного железнодорожного вокзала Владивостока 23 марта 1919г. в 32 вагоне поезда №2051. 38-и летний бухгалтер из Онтарио, Арда был ответственен за доставку в Омск снарядов, гранат, железнодорожных деталей, а также одежды и обмундирования для Белой армии адмирала Колчака.

Арда и его люди столкнулись с рядом проблем по Транссибирской железной дороге: в пути вспыхнул пожар в одном из вагонов со снарядами и взрывателями; после Харбина куда-то исчез локомотив; в результате несчастного случая канадский сержант попал под вагон и потерял обе ноги; в добавок ко всему недельный простой состава посреди Сибири из-за «взорванного большевиками железнодорожного полотна».

В этом длительном и тяжелом пути Арда наблюдал как «сгорела железнодорожная станция», а нерегулярные партизанские отряды устраивали «подрывы рельс», чтобы прервать жизненно важные коммуникации для союзников.7

Канадский военный музей, 20030011-001

Карта России, на которой показано размещение войск и зоны партизанского движения, 1918г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Путь длинной в 4300 км. из «Влади» в Омск поезд Арды прошел за четыре недели. Арда в итоге доставил груз амуниции для армии Колчака, затем две недели он изучал город и проводил время с маленьким канадским отрядом. Он был на концерте в современном здание оперы Омска и посетил церковные службы в большом кафедральном соборе. По наблюдению Арды, настроение в рядах Британской военной миссии было «оптимистическим», Колчак готовился взять командование на фронте и перевести свой военный штаб в Екатеринбург: «Есть впечатление, что союзники будут в Москве к 1 августа, а «все это» кончится к зиме. У меня есть сомнения, но nous verons» (лат. «мы увидим»).8

В мае 1919г. Гарольд Арда вернулся во Владивосток, так последний канадский отряд возвратился с центральной Сибири, по пути обменявшись огнем с большевиками. Месяцем позже был последний инцидент: поезд с пятью полицейскими и 150 лошадьми из Канадской королевской северо-западной конной полиции сошел с рельс в результате диверсии партизан.

Библиотека и архив Канада, коллекция Канадской королевской конной полиции

Вид сошедшего с рельс вагона в результате взрыва партизанской бомбы, Транссиб, весна 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Опыт Арды показывает, насколько тяжким был путь в Сибирь, демонстрирует нестабильность ситуации, что привела в итоге к эвакуации союзников из России. Примерно двадцать транспортных поездов под руководством канадского командования прошли путь в 4300 км. из «Влади» в Омск зимой-весной 1918-1919г. Самая страшная поездка случилась с эшелоном №2209 , по которому партизаны открыли огонь на пути в Екатеринбург.

Девятнадцать вагонов были «раздолблены в прах», погибло двое белых русских солдат и 18 лошадей Канадской конной полиции; за то, что часть груза и большинство лошадей удалось спасти, к медалям были представлены сержант Д.Маргетс и капрал П. Боззард. Далее по железной дороге чехословацкие войска «захватили и повесили 26 большевиков с предводителем за подрыв этого поезда». Один канадец из конной полиции информировал комиссара в г. Регина (Канада): «можно с достоверностью говорить о самой длительной поездке, которую когда-либо приходилось пережить британским лошадям».9

Специальный архив

Примечания

- 1 Operation Order No. 1, 6 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S); Massey, When I Was Young, 211; MacLaren, Canadians in Russia, 165.

- 2 High Commissioner (Chita) to High Commissioner (Vladivostok), 18 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), app. 31; Instructions to Lieutenant-Colonel T.S. Morrisey, 7 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), app. 9; “Operation Order No. 1,” 6 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), December 1918, app. 1. See also diary entries, 8 December to 27 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S).

- 3 “Military Situation, December 31st, 1918,” War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), app. 117; “Twelve Executed for ‘Red’ Uprising,” British Columbia Federationist, 3 January 1919; High Commissioner (Omsk) to Acting High Commissioner (Vladivostok), 30 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S).

- 4 John Ward, With the “Die-Hards” in Siberia, 156; Beattie, “Canadian Intervention in Russia,” 321-22.

- 5 War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), 4 and 5 January 1919; “Pribitiye Kanadskih voysk” [Arrival of Canadian Troops], Pravityel'stvyenniy vyestnik (Omsk), 28 December 1918, Khabarovsk State Archives; War Diary of Force Headquarters, CEF(S), 3-11 January 1919; Morrisey to Elmsley, 15 January 1919, War Diary of Force Headquarters, CEF(S), January 1919, app. B8. See also Kinvig, Churchill’s Crusade, 209-10.

- 6 High Commissioner (Omsk) to Acting High Commissioner (Vladivostok), 9 January 1919, app. 19, Lash to Mewburn (via Elmsley), 13 January 1919, app. 39, Morrisey to Elmsley, 13 January 1919, app. B5 (all in War Diary of Force Headquarters, CEF[S).

- 7 Harold Vernon Ardagh Diary, 23 March 1919-4 May 1919, LAC, Ardagh Fonds, MG 30, E-150, files 2/6 and 3/6.

- 8 Ardagh Diary, 23 March 1919-4 May 1919, LAC, Ardagh Fonds, MG 30, E-150, files 2/6 and 3/6.

- 9 Constable G.H. Pilkington to RNWMP Commissioner, n.d. (1919); Captain Montague Smith to Commissioner RNWMP, 11 August 1919; “Diary of Echelon. 2209”; (all in LAC, RCMP Fonds, RG 18, vol. 3179, file G 989-3 [vol. 2]).

Перейти к

Research Question

Why did Canadians remain in Vladivostok, on the Pacific coast, rather than venture “up country” to the active front against the Red Army in the Ural Mountains?

Key Themes

- • Unreliable supply lines between the Allies in Vladivostok and points “Up Country”

- • Admiral Kolchak’s precarious government at Omsk and the part played by Canada

- • Bolshevik and partisan sabotage along the Trans-Siberian Railroad

Question de recherche

Pourquoi la plupart des Canadiens ont-ils demeurèrés à Vladivostok, sur la côte du Pacifique, plutôt que de s'aventurer dans l'intérieure contre l'Armée Rouge active dans les montagnes de l'Oural?

Principaux thèmes

- • Les lignes d'approvisionnement peu fiables entre les Alliés à Vladivostok et les points stratégiques de l'intérieure sibérien

- • Le gouvernement précaire de l'Amiral Koltchak à Omsk et le rôle du Canada

- • Le sabotage Bolchévik et partisan le long du Chemin de Fer Transsibérien

Исследуемый вопрос

Почему канадцы остались на берегу Тихого океана, во Владивостоке, а не отправились вглубь страны для активных действий против Красной армии в Уральских горах?

Ключевые вопросы

- • ненадежные каналы поставок между союзниками во Владивостоке и частями внутри страны

- • Шаткое правительство адмирала Колчака в Омске и роль Канады

- • большевистские и партизанские диверсии вдоль транссибирской железной дороги

Maps

- Map of Siberia and Russian Far East

- Disposition of forces on Ural Front, October 1918

- Map of Russia showing troop concentrations and areas of partisan strength, c. 1918.

Primary Documents

- Capt. Harold Ardagh's diary from the trip "up country" (coming soon)

- Report on the Military Situation in Siberia, January 1919, War Diary CEFS (coming soon)

- Report on the Political Situation in Siberia, January 1919, War Diary CEFS (coming soon)

- Echelon 2113 Report (derailment of RNWMP train) (coming soon)

- Telegrams showing Japanese-American rivalry (from War Diary Force HQ, Jan 1919) (coming soon)

Multimedia

Secondary sources

- Braithwaite's reminiscences from William Rodney, “Siberia in 1919: A Canadian Banker’s Impression,” Queen’s Quarterly 79, 3 (Autumn 1972): 324-35 (coming soon)

- Richard Orland Atkinson, "Traveling Through Siberian Chaos," Harper's Magazine (New York), November 1918

- John Ward, With the 'Die-Hards' in Siberia (London: Cassell, 1920)

Plans

- Plan de la Sibérie et Extrême-Orient russe

- Disposition des forces sur le Front de l'Oural, octobre 1918

- Plan de la Russie montrant les concentrations de troupes et les zones de forces partisanes, c.1918

Documents primaire

- Journal du Capitaine Harold Ardagh écrit pendant son aventure dans l'intérieure du pays

- Rapport sur la situation militaire en Sibérie, janvier 1919, Journal de guerre de la FECS

- Rapport sur la situation politique en Sibérie, janvier 1919, Journal de guerre de la FECS

- Rapport de l'« Echelon 2113 » (déraillement du train de la RGCN-O)

- Télégrammes montrant la rivalité américano-japonaise (du Journal de guerre du quartier général de la FECS, janvier 1919)

Multimédia

Sources secondaires

- Braithwaite se souvient de William Rodney, « Siberia in 1919: A Canadian Banker’s Impression », Queen’s Quarterly 79, 3 (Automne 1972): 324-35.

- Richard Orland Atkinson, « Traveling Through Siberian Chaos », Harper's Magazine (New York), novembre 1918

- John Ward, With the 'Die-Hards' in Siberia (London: Cassell, 1920)

Карты

- Карта Сибири и Дальнего Востока России

- Размещение войск на уральском фронте, октябрь 1918г.

- Карта России, на которой показано размещение основных военных сил красных и белых, а также партизанские атаки

Первичные источники

- Дневник капитан Гарольда Арда о поездке «вглубь страны»

- Отчет о военной ситуации в Сибири, январь 1919г., Военный дневник Канадских экспедиционных сил

- Отчет о политической ситуации в Сибири, январь 1919г., Военный дневник Канадских экспедиционных сил

- Отчет эшелона №2113 (сход с рельсов поезда канадской конной полиции)

- Телеграмма, демонстрирующая японо-американское соперничество (из Военного дневника Канадского военного штаба, январь 1919г.)

Мультимедиа

Вторичные источники

- Braithwaite's reminiscences from William Rodney, “Siberia in 1919: A Canadian Banker’s Impression,” Queen’s Quarterly 79, 3 (Autumn 1972): 324-35 (coming soon)

- Richard Orland Atkinson, "Traveling Through Siberian Chaos," Harper's Magazine (New York), November 1918

- John Ward, With the 'Die-Hards' in Siberia (London: Cassell, 1920)

English

English Français

Français Русский

Русский